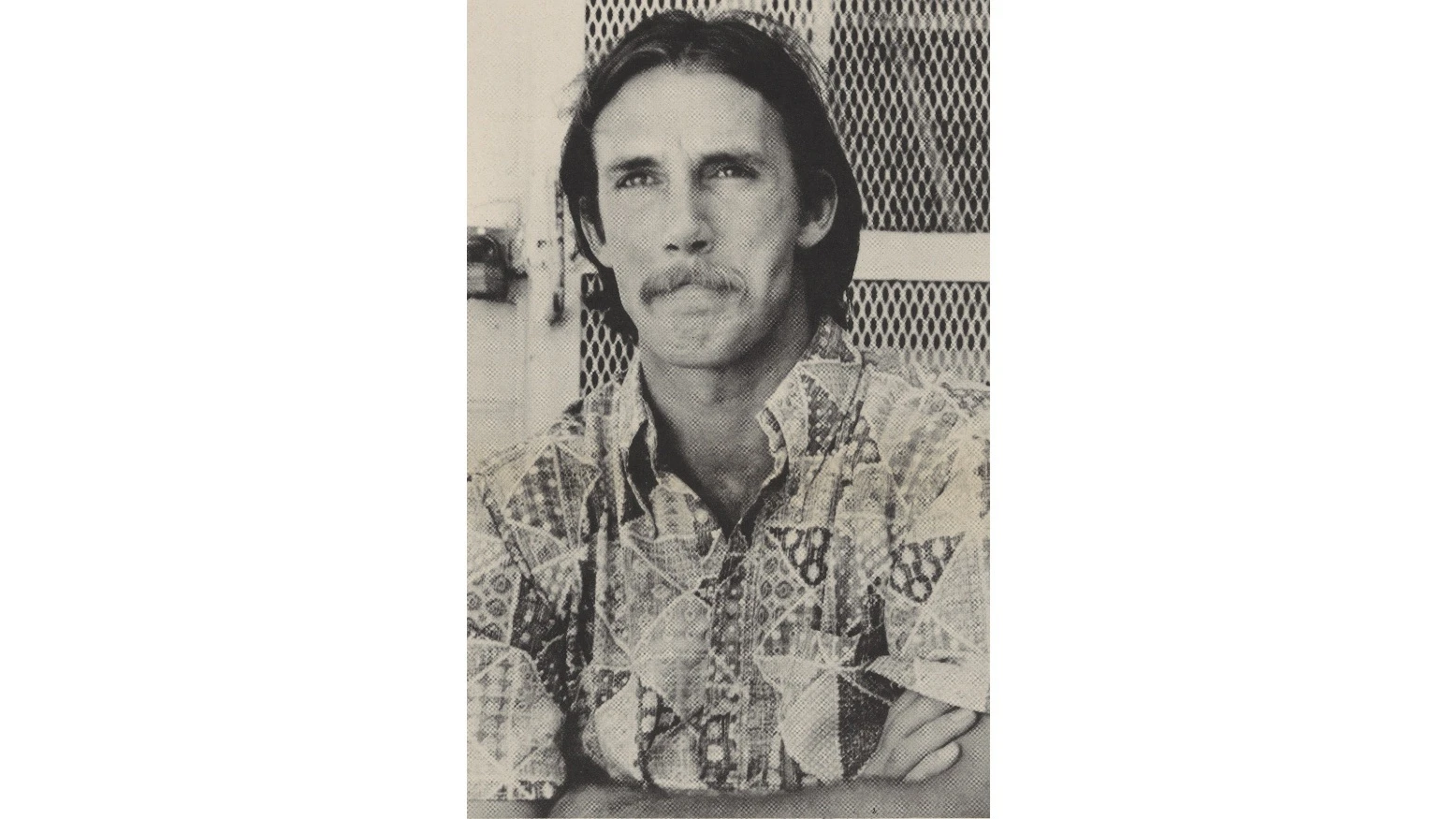

My heart sank when I found out Tom Coffman passed away on December 15, 2025.

Tom and I were very different people of different eras, but we both believed in the power of history.

His early, formative journey into journalism is what drove him into history. To the curious mind that needed to see the root cause of an issue, such a journey was only natural.

“I kept going back and back,” he recalled in 2003. “I kept seeing the events I was covering as a reporter had deeper meaning than appeared on the surface. So I've always been going backward in time!”

Although we were both tall haole with ancestral roots in the Midwestern region of the United States, our generational differences still made us perceive Hawai‘i in ways foreign to one another.

Coffman was born a few years before my grandfather. He arrived in Hawai‘i less than a decade after Hawai‘i’s admission into the American Union.

He got to witness Hawai‘i at a time when the median age in the islands was less than 25. Today, the median age of the average resident is above the age of 40.

It was a young, dynamic place exiting the plantation era. Skyscrapers were being built in Honolulu, while resort complexes replaced sugar cane fields in the Neighbor Islands.

He got to bear witness to a young society eager for dynamism that appeared to slowly fall in upon itself, in large part due to its dependence on the outside world beyond the islands and its failure to properly reckon with those injustices suffered by Hawai‘i’s indigenous peoples.

He bore witness to the formation of the U.S. State of Hawai‘i, starting within the first decade of statehood. His career spanned stints as a journalist, documentarian, photographer, political advisor, lecturer, and general historian.

His unceasing focus, through his decades of reporting and historical story-telling, was Hawai‘i and the evolution of democracy in Hawai‘i.

The Malihini Haole

Coffman arrived in Honolulu on December 3, 1965.

He came of age in the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. In Kanas, the segregation of public schools resulted in national infamy, culminating in a United States Supreme Court case decided in 1954 that ordered the de-segregation of public schools in the town of Topeka.

Topeka was about 30 miles from Tom’s childhood town of Lyndon. He was only entering his teenage years during these legal fights. Segregation’s evils had a tremendous influence on his desire for justice. “I was always interested in writing and I was politicized by the civil rights movement of the 1960s,” he later explained. “Journalism had a tremendous appeal because I felt that, for social change to occur, knowledge had to get out.”

Coffman also knew local politics. His father, Harry T. Coffman, was a Republican legislator in the Kansas House of Representatives. While there, Coffman was employed as a page in the Kansas House, where he ran errands while absorbing their proceedings.

Tom Coffman did not stay in Kansas. He journeyed across the United States, searching for adventure. Eventually, the allure of America's newest state led him to head West. He was a young haole journalist, imbued with the societal activism of the national civil rights movements.

He was part of a new wave of migrants coming to the newly admitted U.S. State of Hawai‘i. While the populations of the Neighbor Islands stagnated during that first decade, the population of O‘ahu exploded, jumping from 500,000 people in 1960 to nearly 613,000 by the end of 1970.

As a result of these migrants, a massive demographic shift also took place. Nearly 100,000 caucasians took up residence in Hawai‘i, primarily on O‘ahu.

While I migrated to the Islands as a little boy at least three decades later, the context of Hawai‘i by that time, I can only imagine, was very different. For one, folks like Tom Coffman had been picking apart the nuances of Hawai‘i’s confused identity as a U.S. State.

“Statehood wasn't the end of history, but a transition to a new history,” he concluded nearly 40 years later. “Statehood allowed Hawai‘i to open up, and to let people assert themselves more, and allowed the genie of the Hawaiian movement to get out of the lantern.”

Before the genie emerged, Coffman needed a political education.

Coffman’s Political Education

Before the age of 30, Coffman assembled a dogged political understanding of this new home, one that became subject to steady revisions in his later years.

Coffman’s journalistic education in a small state full of tight-knit communities dominated by a single political party and limited economic opportunity seemed to prepare him for his later foray into Hawai‘i society.

In his involvement, Coffman exercised his craft as a foreigner. His listened, learned, and took what he gathered to new places because people’s thoughts were the foundations of future conversations. As a result, his observations compounded into grand portraits. He, like Alexis de Toqueville in the United States of the 1830s, carried a special ability to observe the nuances of a society to which he was a newcomer.

When he first started at the Honolulu Advertiser in 1965, Coffman covered such topics as the state’s rush to construct highways, the mismanagement of the Ko‘olau Boy’s Home and Kawailoa Girl’s Home, and the state’s role in the national War on Poverty.

In February 1967, he took a break from journalism, working as a field coordinator form the Honolulu Community Action Program (HCAP). It was a brief stint, but the experience spoke to his abiding interest in social activism.

By January 1968, he was back in journalism as a political writer with the Star-Bulletin, the other major newspaper at the time in Honolulu. While there, he covered the 1968 Legislative Session, labor relations, the 1968 Constitutional Convention, the 1968 re-election of Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi and the consolidation of the Democratic Party’s control over all of Hawai‘i’s major state and county offices, along with the rise of President Richard M. Nixon.

In particular, his careful coverage of the 1968 Constitutional Convention gave him unique insight into many of the event’s key actors, including such leaders as Robert Taira, John Ushijima, Nelson Doi, George Ariyoshi, Pat Saiki, and Frank Fasi, to name a few.

The relationship between land and power became another key source of coverage. In Honolulu, Governor John A. Burns’s attempt to hasten the development of Magic Island elicited statewide controversy. Beyond Magic Island, however, there was also the Boise Cascade scandal.

Boise Cascade and the 1970 Elections

The story of the Boise Cascade Scandal of Hawai‘i Island opened Coffman to the story of land and power in Hawai‘i. Like some plot out of a neo-noir film, it was a story that forever shaped his understanding of the Islands.

“The story is one of people, land, money, and the byplay between Hawai‘i governmental agencies and a corporate giant,” Coffman explained in early 1970. “It revolves on questions of conservation and development, politics and ethics, plus recent public combat which could define the shape of things to come.”

It was a story which few journalists or newspapers would likely be able to pursue in the present day. As he explained, “the research extended over week, then months: a Mainland tour, a trip to the Big Island, correspondence, studying other newspapers’ files, conducting dozens of interviews, reading and more reading, then writing and re-writing.”

While bits and piece of the story had emerged in the years before Coffman published his multi-part series, no one had ever assembled the full plot before that point. The research spoke to the democratic power of investigative journalism.

In short, Coffman broke down a plot by the Boise Cascade company to use a legislator to facilitate the re-development of thousands of acres along the Kona Coast. Sen. John Ushijima, in a private capacity, had evidently arranged for the re-zoning of over 2,900 acres of land along the Kailua-Kona Coast from agricultural to urban use before the State Land Use Commission.

Such a maneuver would have prefaced the subsequent re-development of this land into a resort-residential zone. Ushijima’s representation of Boise Cascade before the Land Use Commission mixed with his official duties in the State Senate, where he served as Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Hawai‘i Island Select Committee.

In the Senate, Coffman unearthed Ushijima’s efforts to advocate for Senate Bill 259 in the 1969 Legislative Session. The measure had been co-written by Boise Cascade attorneys.

If passed into law, Senate Bill 259 would have enabled the company to function as a pseudo-county within Hawai‘i Island.

Ushijima’s efforts overlapped with the massive amounts of money that the Burns administration was pouring into Kailua-Kohala, largely to bolster the development of infrastructure for hotels and resorts along the coastline amidst the decline of sugar plantations throughout that region.

State Senator Eureka Forbes, a Republican from O‘ahu, praised the Star-Bulletin for its willingness to confront the Boise Cascade matter. “Land use law and process, being extremely complex, is conseqently a very sophisticated political issue, one rarely discussed and little understood by the general public.”

Coffman set a critical standard for investigative journalism in the state. “The resulting increased awareness of an enlightened public can only be good for Hawai‘i.”

The story laid out the economic cost of poorly-planned development in the new Hawai‘i. He was begining to understand the political significance of Governor Burns’ investment in infrastructure along the Kona-Kohala Coast, where much of Boise Cascade’s development had been planned. It also likely weighed on Coffman as he began to watch the Democratic Party devolve into infighting in the August 1970 primary for the party’s nominee for governor.

Given Coffman’s accruing knowledge of state politics, close relationships with a wide plethora of sources, and general observational skills, he was positioned to document growing inter-party tensions within the Democratic Party, most notably the split between Governor John Burns and Lieutenant Governor Tom Gill in 1969. His coverage of the 1970 Gubernatorial Election resulted in "Catch a Wave," a early classic of Hawai‘i’s political history as a U.S. State.

While he had already been established as a serious investigative journalist with a nuanced view of Hawai‘i’s politics, the work took Coffman to a new stage in his writing career. "Catch a Wave’s" publication in 1972 set the stage for Coffman’s independence. It was clear he wanted to pursue more longer-form writing projects.

Before he became an independent writer, however, Coffman still worked as a reporter. The length of his stories began to grow into longer-form investigations.

Coffman’s growing awareness of money’s influence on politics resulted in an unprecedented 13-part series known as ‘High-Priced Politics.’ The series uncovered the rising cost of successful campaigns in Hawai‘i politics and the increasing reliance of several political figures on campaign contributions from architects, construction companies, and other professions tied to development and land use.

The investigation took shape after his publication of "Catch a Wave." If he had conducted the investigation before "Catch a Wave’s" publication, his views on Governor Burns’ ability to win re-election may have shifted.

It was more than a grassroots effort by a beleaguered incumbent. As part of the investigation, Coffman peeled apart the existence of a one-million dollar campaign fund put together by Governor Burns. This fund’s unprecedented size was equivalent to $8.3 million in 2025 dollars.

Even by today’s standards, it was a major sum. For contrast, OpenSecrets estimates that then-Lieutenant Governor Josh Green raised $3,655,289 between 2021 and 2022. Governor David Ige raised $2,638,678 between 2017 and 2018.

However, the investigation still inspired reform. The series set the stage for the passage of a comprehensive campaign spending reform act (Act 185) on May 23, 1973.

His series on campaign spending also inspired another budding journalist, George Cooper. Over the course of the next decade, Cooper investigated the relationship between political officials, appointed bureaucrats, and re-zoning of land from agricultural to urban purposes across the state. As a result of the work, Cooper (with Gavan Daws) published "Land and Power in Hawai‘i: The Democratic Years" in 1985. Cooper disclosed Coffman’s influence in a November 2022 essay published shortly before his own passing in November 2023.

Tom Coffman eventually left journalism to get involved in politics. While his authorship of "Catch a Wave" is well-known, his later involvement in Tom Gill’s campaign for Governor in 1974 alongside Byron Baker is not. He left the Star-Bulletin in 1974 to advise Gill’s campaign on policy. Beyond journalism, Coffman believed in reform through the political game.

In the 1974 elections, Coffman ran as a candidate for an O‘ahu seat on the Board of Eduction. There were seven open seats and 26 candidates. By only 600 votes, Tom placed eighth in the race.

Beyond Journalism

By October 1974, Tom had gone into business as an independent freelance writer and researcher. It opened a key phase of his professional life that lasted half a century.

While Coffman’s early career as a muckraking journalist was only one part of his career, I personally think it was a formative part of his journey. As a result of this period, Coffman learned how to tackle any topic with finesse, nuance, and sharp research. People were not sources for a story; they were living parts of a nuanced society whose contradictions Tom loved dearly.

In June 1972, Coffman laid out a clear agenda that would constitute decades of research. Even then, he knew what he wanted to do over the next half-century. “There are a whole hell of a lot of books on Hawai‘i that should be written, that I’d like to see written,” he declared.

“There should be a detailed book on the wartime experiences of AJAs here. That was the turning point of Hawai‘i that put us where we are today. There needs to be a book on the plantation way of life, capturing it before it dies out. At least for now, kids should be sent out with tape recorders to talk to the old people about their experience, so the material will be there.”

This particular interest led to one of Tom’s first freelance projects. It was a biography of H.S. Kawakami’s story, a major grocer, Japanese migrant, and father of then-State Representative Richard Kawakami.

Kawakami’s story was only the first one in a series that charted the stories of Hawai‘i’s Japanese-American diaspora. "Taidama!" was one such work, along with the earlier "I Respectfully Dissent," a biography of former Hawai‘i Supreme Court Justice and labor attorney Edward Nakamura.

My favorite of his works was "Inclusion," a 2021 work that uncovered the multi-ethnic fight to preserve the civil rights of Japanese residents in the Territory of Hawai‘i during the Second World War. This work was the result of an earlier documentary crafted more than a decade earlier.

There were other interests. “The hardest one to describe would be a book on the Polynesian viewpoint on life. The communal feeling, and the feeling for nature and the land, are values which have been unworkable in our profit-oriented Western society. Now, once again, these are returning as relevant values. What their life was all about — is still all about, for some people — could be a guide to everyone’s future.”

Through Tom Coffman Communications, he branched off into audiovisual and documentary work, producing multi-media slideshows for such clients as the County of Kaua‘i and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. By 1980, he was also involved as an early publicity officer for the Hokule‘a as part of the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Coffman’s later work included several documentary films, many of which have been re-published online for new generations to discover. "O Hawai‘i" is a major documentary that re-cast the history of Hawai‘i. As recently as September 2025, Coffman’s work on "O Hawai‘i" was celebrated following the first Hawaiian History Month.

Tom followed stories wherever they took shape. Several other documentaries told the stories of other ethnic groups that journeyed to Hawai‘i, such as the Koreans ("Arirang") and Japanese communities ("Ganbare!"). Many of these projects were inspired by his earlier involvement with the Hawai‘i Multicultural Awareness Project, an effort that took shape between the late ’70s and early ’80s.

Later, Coffman produced a documentary in 2009 on the legacy of Ninoy Aquino, a politican who was assassinated in Manila for his opposition to the dictatorial regime of President Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. Aquino’s assasination later triggered a political revolution that resulted in Marcos’ exile in Honolulu.

Coffman, as an independent journalist, documented the rise of community organizations in the middle of the ’70s for the Hawai‘i Community Action Program (HCAP). Social work always fascinated Tom, and it resulted in the publication of a monograph which examined eight influential social workers in Hawai‘i.

Tom’s works were always an expression of what he found most important to Hawai‘i. If no one else was documenting a story, he knew it needed to be told.

Coffman’s Political Worldview

With the environmental movement of the ’70s, Coffman began to document the cost of poorly planned growth marked by the haphazard re-zoning of agricultural lands for the sake of urban sprawl. He documented the development of Moanalua in some depth. At the end of the ’70s, he also wrote a booklet on the evolution of the Honolulu Board of Water Supply. Decades later, he produced a documentary on the sacred nature of Hawai‘i’s forests.

Like his support for Tom Gill in 1974, his influence over former Governor George Ariyoshi’s legacy is more often forgotten. Coffman helped memorialize the legacy of Governor George Ariyoshi. These works were not strict works of history, as Ariyoshi’s memoir omitted any reference to Larry Mehau or the construction of the Interstate H-3 on O‘ahu. He conducted the oral history of former Governor George Ariyoshi, a monumental work conducted under the Center for Oral History. Published in 2016, the full interviews are freely available online.

He facilitated the publication of Ariyoshi’s memoir in 1997 and advised Ariyoshi’s 2020 book "Hawai‘i’s Future." Coffman also worked with Ariyoshi in 2009 on "Hawai‘i: The Past Fifty Years, The Next Fifty Years." Thousands of copies of this work were distributed across schools in the State as part of a statewide essay contest that asked students about their vision of Hawai‘i future. I still remember getting a copy when I was a high school student in ‘Aiea.

Coffman never forgot the hours he spent interviewing Burns, who shared his theory of Hawai‘i’s political evolution in the run-up to the 1970 Gubernatorial Election. Coffman later detailed those experiences at an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the founding of the John A. Burns School of Medicine in May 2025.

When Tom wrote a history of the modern State of Hawai‘i in 2003, he recognized that the ’70s were the period where the conflict between unplanned development and environmental degradation became stark. It was also a period where the Native Hawaiian Civil Rights movement became a central part of the state’s politics.

"Nation Within," which was based on Coffman’s book of the same name, narrated the history of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in a U.S.-backed coup. Coffman’s production of the document was one attempt to tell history beyond the bounds of the written word.

His efforts to reckon with the legacy of historical injustice against Hawaiians, as perhaps best magnified by the overthrow, inspired his history. History, to that end, was not a passive device for the nostaglic. It was a tool for bulldozing societal inaction.

“In the press for a system of reconciliation and redress for Native Hawaiians, we will sooner or later establish a Native Hawaiian governing entity,” Tom predicted in 2010. “There will be a necessarily contentious negotiation of the associated issues of land and water — specifically those that belonged to the Hawaiian kingdom and the Hawaiian monarch.”

In 2025, Coffman found Hawai‘i a confused place in need of history more than ever.

Where I Remember Tom Coffman

We might’ve met for breakfast at Kam Bowl in Kalihi, ice cream at the Zippy’s on Vineyard, or via phone call. Regardless, the talk story nature of our conversations was always a treat.

Tom sought a sustainable course of Hawai‘i and its democracy, one that would continue after his passing. History was a means to this end.

He knew I was frustrated with Hawai‘i, and he was frustrated too. Yet he always tried to push me to channel that frustration into research. Resignation with circumstance was never productive.

In his later years, Coffman called for the ‘re-invention’ of Hawai‘i. “As when we spoke optimistically about the noble possibilities of statehood, in that same spirit we can engage optimistically in a search for how a reinvented Hawai‘i might work,” he said in 2010. “The project called the State of Hawai‘i in its present configuration is temporal, but Hawai‘i is timeless.”

I think this is the point in his intellectual journey where I actually met Tom Coffman, in part thanks to my research into the 1978 Constitutional Convention. Coffman saw the 1978 Constitutional Convention as the watershed political moment in state history. It appeared as an unprecedented chapter in Hawai‘i’s experimentation with democracy.

Any conversation about the future of Hawai‘i always turned to the lofty agenda of the 1978 Constitutional Convention and the present-day debates over Hawaiians over their own political future. It was a conversation which turned to such developments as Mauna Kea. If Tom had time for another project, I personally wish he might have pursued an environmental history of Mauna Kea’s management over the past century.

Tom leaves behind a lot of unfinished work. It will fall on those who survey his legacy to see what remains undone. The work was infinite.